After the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb in 1949, the American public was understandably nervous. They were aware of the destruction that individual atomic bombs did to the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But the general public did not know a lot yet about the dangers of radiation and fallout.

So, a new Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) was set up in 1951 to educate – and reassure – the country that there were ways to survive an atomic attack from the Soviet Union. They commissioned a university study on how to achieve “emotion management” during the early days of the Cold War.

“Dropping immediately and covering exposed skin provide[s] protection against blast and thermal effects ... Immediately drop facedown. A log, a large rock, or any depression in the earth’s surface provides some protection. Close eyes. Protect exposed skin from heat by putting hands and arms under or near the body and keeping the helmet on. Remain facedown until the blast wave passes and debris stops falling. Stay calm, check for injury, check weapons and equipment damage, and prepare to continue the mission.” — US Army field manual FM 3–4 Chapter 4.

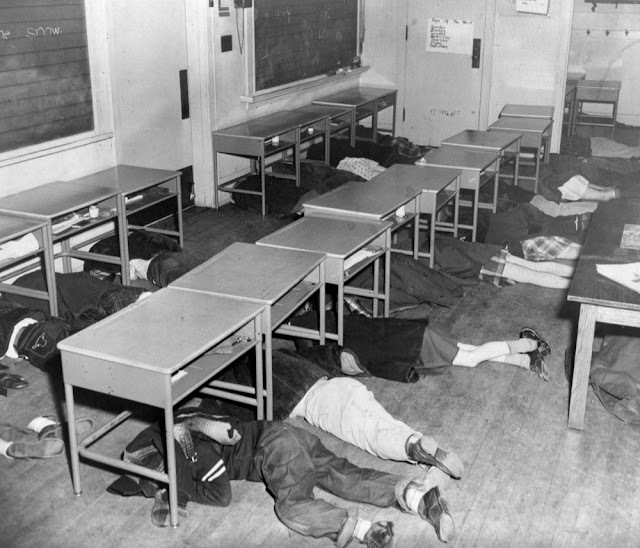

One of their approaches was to involve schools. Teachers in selected cities were encouraged to conduct air raid drills where they would suddenly yell, “Drop!” and students were expected to kneel down under their desks with their hands clutched around their heads and necks. Some schools even distributed metal “dog tags,” like those worn by World War II soldiers, so that the bodies of students could be identified after an attack.

The next logical step was to promote these “preparedness” measures around the country, and the FCDA decided the best way to do that was to commission an educational film that would appeal to children. In 1951, the agency awarded a contract for the production to a New York firm known as Archer Films.

Archer called in teachers to meet with them and got the endorsement of the National Education Association. An administrator at a private school in McLean, Virginia, mentioned that they had participated in the “duck and cover” drills. That was the first time the producers had heard the drills called that, and they thought the phrase would work as a title.

The producers went to work on a script that would combine live actors and an animated turtle to encourage kids to duck down to the ground and get under some form of cover – a desk, a table or next to a wall – if they ever saw a bright flash of light. The flash would presumably be produced by an atomic blast. The hero of the film was the animated Turtle named Bert who wore a pith helmet and quickly ducked his head into his shell when a monkey in a tree set off a firecracker nearby.

When Duck and Cover was completed in January 1952, its admonition perhaps could have saved some lives in the event of an atomic-bomb attack. Civil Defense officials liked the animated turtle and his monkey tormentor so much that they included the film in the “Alert America Convoy.” The convoy had 10 trucks and trailers that toured he country for nine months in 1952. Each vehicle contained civil defense dioramas, posters, 3-D models and a film theatre showing Duck and Cover and other educational movies. The theme was practical ways individuals could “beat the bomb.” According to the FCDA, 1.1 million people eventually saw the convoy exhibits.

At the same time, Duck and Cover was premiered to educators at a gala screening at a Manhattan movie theatre. From there, it was distributed to schools around the country by one of the largest educational film distributors. It was shown on television stations around the country, and some educated guesses put the TV audience in the tens of millions.