Jane posing with her husband of 11 years, Gilbert, and their three kids Pamela, 4, Tony, 5, and Peter, 7, in front of the large two-story house they lease.

In 1941, LIFE magazine decided to document the lives of one of the biggest single demographics in the U.S.: the 30 million housewives who did most of the washing, made beds, cooked meals and nursed almost all the babies of the nation, with little help, no wages and no other jobs.

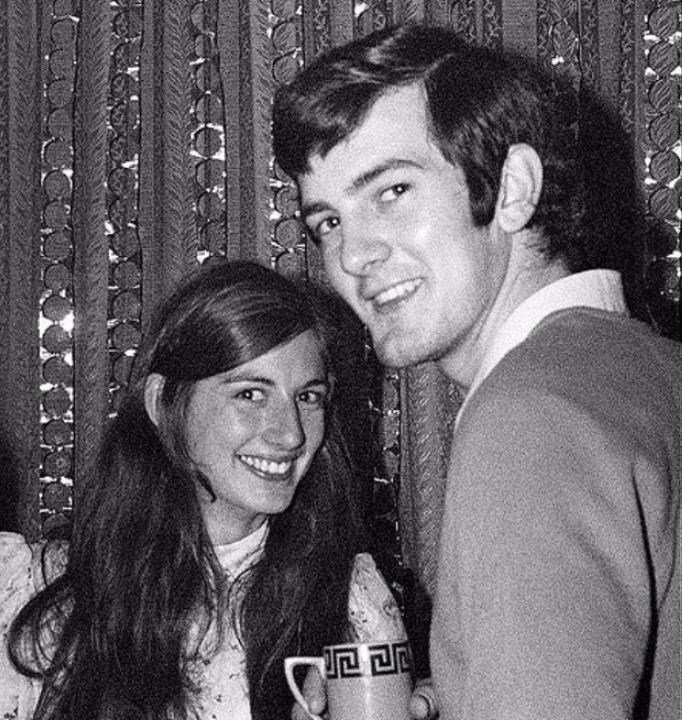

The magazine chose Jane Amberg from Kankakee, Illinois as its subject, a “modern, young, middle-class housewife.” Around 1927, she went on a blind date with Gilbert Amberg. Three years later they were married, when Jane was 21. LIFE documented the jobs Jane performed to make sure their household ran smoothly.

It represented the responsibilities of millions of other American women at the time: seamstress, chauffeur, laundress, chambermaid, cook, dishwasher, waitress, and nurse. In Jane’s case, a maid came in occasionally to vacuum the floor and wash the windows, at $0.35 per hour.

Through all of this, Jane had to be her husband’s “best girl” outside the home. Once per week, the couple went to dinner, the movies, or visited friends. They also entertained at home. All this would soon change. Just over two months after the article was published, the Japanese navy launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. America entered World War II.

Jane shushing her husband Gilbert, as they sit having a quiet 6:30 a.m. breakfast before their three kids wake up, in the kitchen at their home.

World War II changed both the type of work women did and the volume at which they did it. Five million women entered the workforce between 1940-1945. The gap in the labor force created by departing soldiers meant opportunities for women. In particular, World War II led many women to take jobs in defense plants and factories around the country.

These jobs provided unprecedented opportunities to move into occupations previously thought of as exclusive to men, especially the aircraft industry, where a majority of workers were women by 1943.

Social commentators worried that when men returned from military service there would be no jobs available for them, and admonished women to return to their “rightful place” in the home as soon as victory was at hand.

Although as many as 75% of women reported that they wanted to continue working after World War II, women were laid off in large numbers at the end of the war.

But women’s participation in the workforce bounced back relatively quickly. Despite the stereotype of the “1950s housewife,” by 1950 about 32% of women were working outside the home, and of those, about half were married. World War II had solidified the notion that women were in the workforce to stay.

Jane busy straightening up before launching into some heavy cleaning with dust mop and carpet sweeper.

Jane making one of the four beds she does daily, after doing breakfast dishes and getting the kids to school.

Jane scrubbing the bathtub in bathroom at home.

Jane standing on ladder to place special china plate as decoration above the doorway in the living room, which she decorated herself, as her son Tony plays on the floor.

Jane loading the automatic washing machine with several days’ dirty clothes, in basement at home.

Jane conferring with a mechanic at gas station about the car she uses to chauffeur her husband to and from his office, plus get the children back and forth to school.

Jane serving lunch to her husband Gilbert, who has come home from the office a few minutes away, and her ever-present kids.

Jane with Peter, Tony and Pamela, as they go to the drugstore to buy ice cream cones, after the boys had haircuts at local barbershop in town.

Jane using pop-up toaster, as she makes sandwiches for her three children.

Jane rapping admonishingly on the window in the background as she oversees her kids Peter, 7, climbing the slide ladder, while Tony, 5, blocks the slide, and Pamela gets kicked out of the tent while playing with a neighbor’s children.

Jane bathing her daughter Pamela, 4, before dressing her for bed at night.

Jane prepares for dinner party by carrying a roast beef platter to the dining table she has carefully set with colorful placemats, silver candlesticks and silver centerpiece with flowers and a bottle of Chianti, as her guests finish cocktails in the living room.

Jane chatting with her dinner guests Mr. Bert Miller and wife, as her husband Gilbert stands behind her, carving a roast beef to be served at the table.

Jane dancing with her husband Gilbert (third from left) amidst other couples at their country club’s formal dance.

Jane mending a pair of socks as she lounges in bedroom while listening to her favorite jazz records during her leisure hours (time with out kids).

(Photo credit: William C. Shrout / Life Magazine).